With the growing popularity of youth climbing (and competitions), there are more myriad kid climbers now training hard and pushing their limits. But these youth climbers must not train exactly like their adult counterparts! This article provides guidelines for age-appropriate training for climbing that’s both effective and safe.

(This article was originally published in January 2015.)

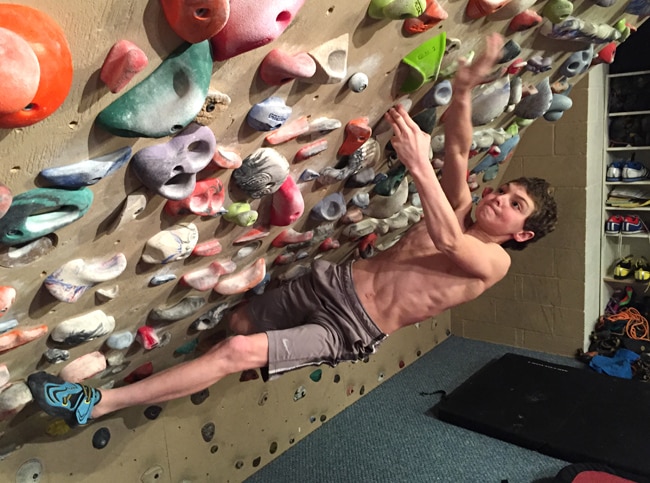

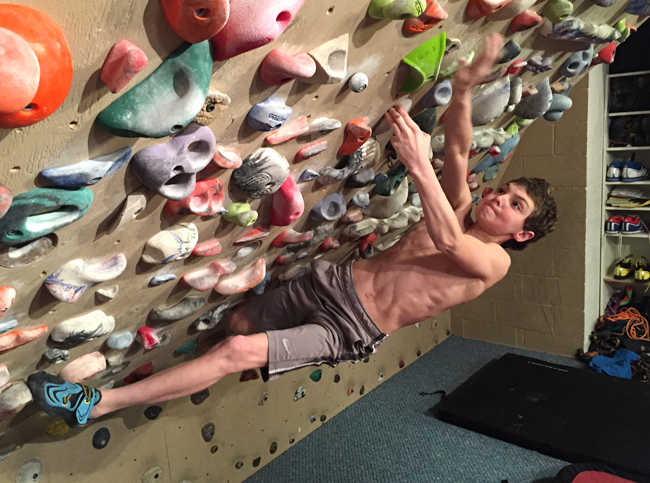

With the growing popularity of youth climbing competitions plus the recent press on preteen climbers sending V10 and 5.13 routes, many parents—and some coaches as well—jump to the conclusion that these elite youth climbers must be involved in some secret, arduous strength-training program. No doubt, this speculation has led plenty of aspiring youngsters to unnecessary and potentially dangerous exercises. In truth, however, youth climbers reach elite levels mostly as a result of consistent practice, high-quality instruction, their featherweight prepubescent physique, and sometimes the genetic blessings of uncommon flexibility, grip strength, and power. Simply climbing three or four days per week for several years is enough for many of those who start young to develop the ability to pull through steep terrain on tiny holds with an efficiency and ease that can make a grown man weep!

Climbing is a skill sport, and therefore time spent climbing–learning technical and movement skills–is the most important form of training for climbing.

Given this, there’s no harm (and a good amount of benefit) in having youth climbers do a limited amount of strength training. Disregard any old wives’ tales you’ve heard that “strength training is not for kids” or that “strength training will stunt a youth’s growth.” The American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Sports Medicine both support basic strength training for kids. The exercises must simply be age-appropriate, not overly dynamic or stressful, well-monitored for proper form.

So what are the age-appropriate exercises for youth climbers? Let’s take a look across three categories: ages six through nine, ten through fifteen, and sixteen through eighteen.

Ages 6 – 9

Prior to the adolescent growth spurt, most apparent gains in strength come from motor learning, not hypertrophy (muscle growth). Any manner of extensive strength training is unnecessary and largely a waste of time at this age. Motor learning comes when adaptations of the nervous system—specifically, improved coordination and synchronization of muscular motor units (groups of muscle fibers that fire together)—lead to a greater expression of strength and power. Therefore, movement-oriented training should be the backbone of every workout. Developing climbing-specific strength, then, is simply a matter of following through with a consistent schedule of climbing. This will yield measurable gains in strength despite little or no change in muscle size.

Incorporating a few supplemental climbing-like exercises is fine. This just shouldn’t take away from movement training and climbing-for-fun time. Body weight exercises such as pull-ups, push-ups, abdominal crunches, and other similar gymnastic movements are the only strength-training exercises needed at this age.

Antagonist muscle training (pushing motions) is also an essential part of youth training-for-climbing program to prevent muscle imbalances that can lead to postural problems and injury.

Ages 10 – 15

After a year or more of climbing experience and assuming a solid command of technical skills, it’s appropriate to introduce a moderate amount of strength training for climbers aged ten to fifteen. These are the years of the adolescent growth spurt. Peak height velocity occurs at age 11.5 for girls and age 13.5 for boys. Changing hormone levels will lead to noticeable muscle growth as weight velocity peaks between twelve and fifteen.

It’s during this period that some fast-growing youths perceive a distributing decrease in strength-to-weight ratio. This is because their weight gain outpaces their strength gains. Once again, quality coaching is critical so that concerned youth climbers understand why they are apparently getting weaker despite a consistent climbing schedule. Some misguided youths will react by beginning a strict diet or extensive strength- or power-training program (or both) in an attempt to regain their physical capabilities. This response is both unfortunate and unhealthy, and it often ends in injury, anorexia, or burnout.

A good coach will explain the changes that all youth climbers face during puberty. This way climbers can understand how the process will lead them to a physique that is stronger, taller, more powerful, and supremely capable of climbing at a very high level. The coach should gradually introduce both general and sport-specific strength-training exercises that will train the new muscle to be more efficient and effective for performing in the vertical plane. This also helps reduce injury risk as the growing youths attempt harder climbs.

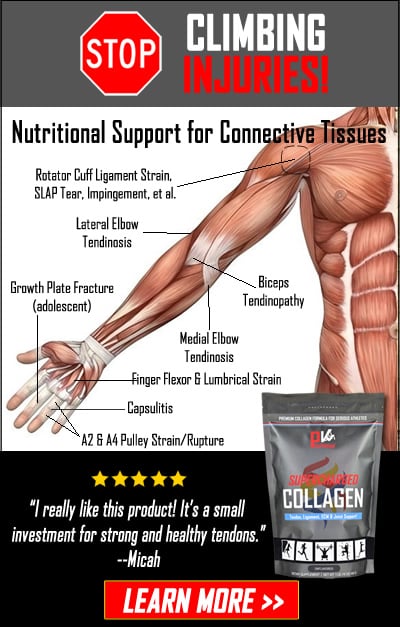

While the overriding training emphasis should remain on the development of outstanding climbing technique and mental fortitude, youth climbers can safely engage in 20-40 minutes of strength training three days per week. Climbing-specific exercises such as pull-ups, lock-offs, fingerboard pull-ups and hangs (in small doses), slow, controlled campus laddering (never double dynoing!), and various core-strengthening routines should be executed on climbing days, not rest days. Most important, the youth should avoid the most advanced and stressful exercises (as used by older elite climbers). This includes double-dyno campus training and high-resistance hypergravity isolation training (HIT), as these can lead to growth plate fractures in the fingers and a necessary withdrawal from climbing for an extended period.

Perhaps the most important addition to a youth’s training program is a small number of exercises targetting the muscles that oppose the prime movers in climbing. A regular climbing schedule (even without use of climbing-specific strength exercises) will lead to significant gains in pull-muscle strength: the prime movers for the vertical athlete. Maintaining stable joints and proper posture, reducing injury risk, and pursuing peak performance in climbing demands a small commitment to training the antagonist push muscle of the upper body. Specifically, the training should target the extension-producing muscles of the chest, shoulders, and arms, and the small muscles of the rotator cuff. A modest investment—just fifteen to twenty minutes, two or three days per week—will strengthen these important, yet often overlooked, muscles. The process will vastly reduce the risk of the elbow and shoulder injuries common among avid and expert climbers alike.

Most of the necessary climbing-specific and antagonist-muscle-training exercises are described earlier in this book (consult Conditioning for Climbers for other options). For the antagonist muscles, I suggest beginning with:

- Two sets of push-ups, one or two sets of dumbbell shoulder presses

- Two sets of dips (with assistance, if needed)

- One set each of external and internal rotations of the shoulder

Each exercise should be performed with relatively light weight that allows twenty to twenty-five repetitions. These exercises can be performed at the end of a climbing workout or on rest days from climbing.

A final facet of effective training for youth climbers involves flexibility training. While most climbing moves don’t require extraordinary flexibility, quickly growing bones and muscles can lead to an increasing sense of tightness that may somewhat limit movement on the rock. A moderate amount of daily stretching can go a long way toward maintaining smooth, flexible movement. Gentle stretching of the arms, torso, and legs should be performed as part of a more comprehensive warm-up before engaging in maximal climbing. Further, engaging in ten to fifteen minutes of stretching each evening (while watching TV or during quiet time before bed) is highly effective in helping relax and lengthen the tired, growing muscles of a hardworking youth climber.

Ages 16 – 18

As youth climbers approach their adult height, they can begin a gradual transition into a more intensive climbing-specific training program. Still, growth plates remain vulnerable to injury; they may not fully fuse until around age twenty. What’s more, increases in training volume and magnitude can lead to overuse and acute injuries of the fingers, elbows, and shoulders. For these reasons and more, a fully-engaged and informed coach or climbing parent is highly beneficial during this transition into becoming astute, self-directed adult climbers.

Many of these late-teen climbers will already be highly accomplished, and a few will possess world-class capabilities. Elite-level training techniques, such as one-armed pull-ups, campus laddering, and weighted bouldering (with a 10-pound belt, for instance), can be added incrementally during this multiyear ramp-up period. However, hold off on fully dynamic double-dyno campus training and advanced hypergravity-training protocols until after the eighteenth birthday (or even later in the case of a late bloomer). Strengthening the antagonist muscle groups remains essential for muscle balance, proper posture, and reducing the risk of elbow and shoulder injuries—all potential issues for hard-training late-teen and twenty-something climbers.

The Complete Climber

All the while, it’s imperative that the training program remain focused on improving the complete climber, including mental and technical training. A narrow, impulsive quest for greater strength and power is not the sole pathway to improvement. Youth climbers going through puberty and maturation should be reminded frequently that sharp advances in ability often result from mental breakthroughs. Becoming a true master of rock comes only by way of gaining vast experience on a wide range of climbing walls and rock types. Toward this end, a good coach will constantly dovetail physical training with ongoing instruction on advanced climbing techniques, tactics, and the many facets of the mental game. The most thoughtful and introspective teenagers will be ready to look into the book Maximum Climbing: Mental Training for Peak Performance and Optimal Experience. This is a challenging text that explores powerful metacognitive skills to enhance performance in climbing as well as many other life endeavors.

Beyond the above tips, the complex details of an advanced youth training program are outside the scope of this book; hire an experienced climbing coach, or consult Training for Climbing to develop an intelligent, self-directed program.

Youth Training Articles by Hörst (please share with fellow coaches and youth climbing parents)

- Overview of Training for Youth Climbers

- Skill Development of Youth Climbers

- Cognitive Development of Youth Climbers

- Youth Climbing Injuries and Prevention

Copyright © 2000–2023 Eric J. Hörst | All Rights Reserved.