The lumbricals are a family of muscles that all climbers use, but perhaps have never heard of. If you aspire to climb hard—or already do!—then some knowledge of lumbrical function, training, injury risk and treatment will be empowering.

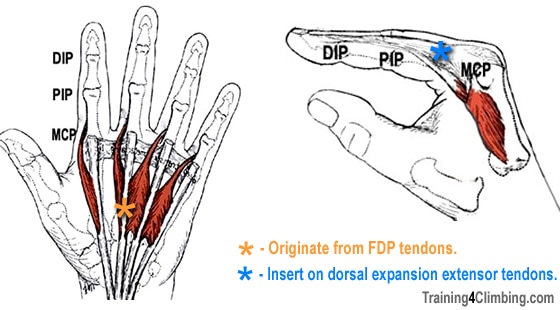

Located in palm of the hand, the lumbricals are a unique muscle group in form and function. First, although most muscles originate and insert onto fixed attachments (bones), the lumbricals originate from the tendon of the powerful flexor digitorum profundus (the forearm muscle that flexes the DIP finger joint). The four lumbricals insert on the flat tendons of the extensor expansion near the MCP joint. Interestingly, due to the mobile attachment points, the lumbricals produce both finger extension (of PIP and DIP joints) and flexion (MCP joint).

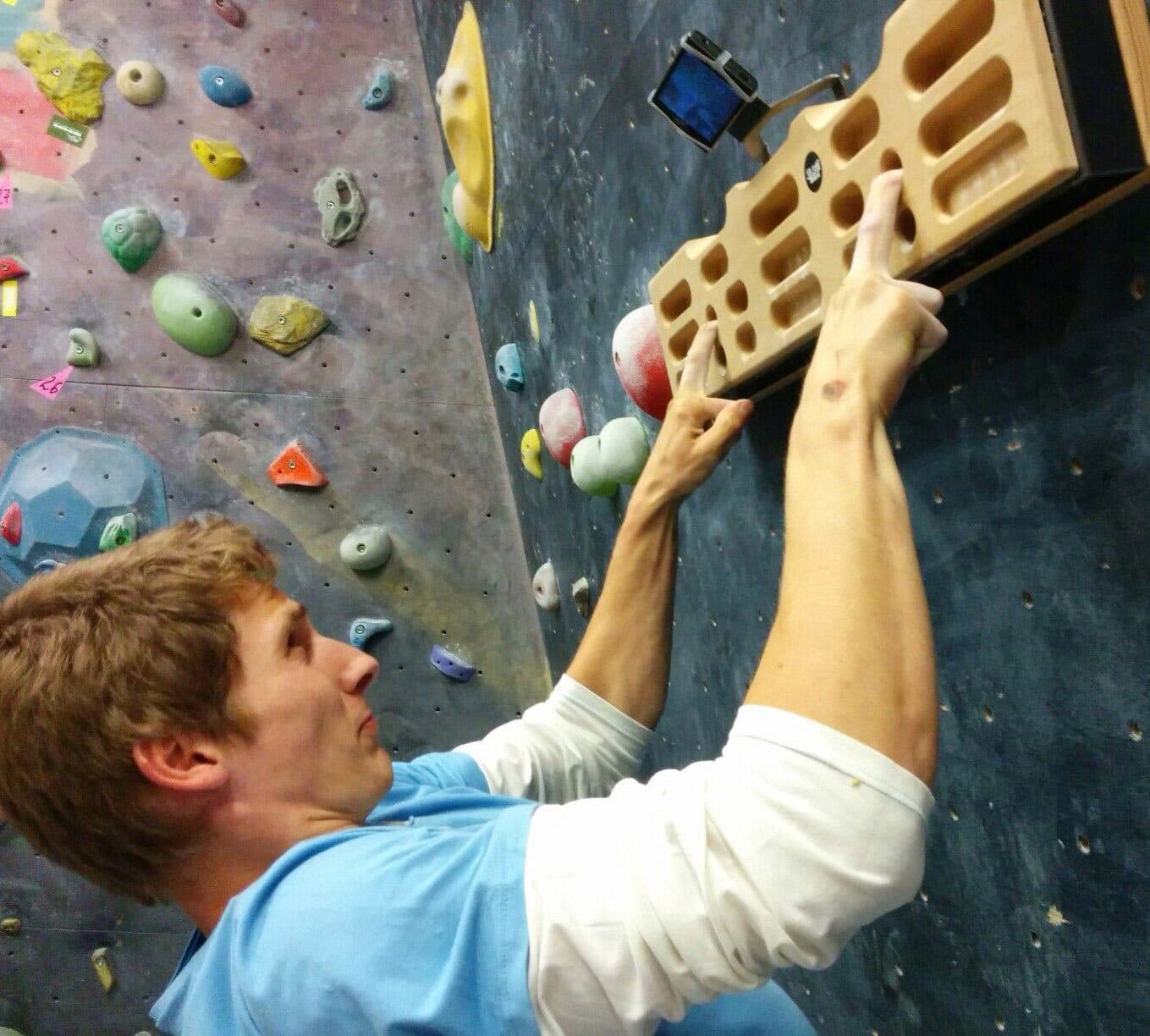

While not a major contributor to finger force production, the lumbricals provide important sensory feedback and fine motor control of the fingers. They also contribute an estimated 10 percent towards force production in the hand, perhaps most importantly when the MCP joint flexes with extended fingers—in climbing, this “L”-shaped hand position is common when pinching (right photo), clinging to a deep square-cut jug hold, and cupping a hand jam.

Lumbrical Injuries on the Rise

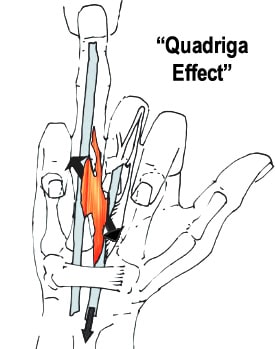

Central to a lumbrical injury is the so called “quadriga effect”. When one finger is extended while the others fingers are flexed—as in pulling on a one-finger pocket—a novel shearing force can strain or tear a cold, inflexible, or poorly trained lumbrical muscle. Injury can range from Grade I (quickly healing microtrauma) to Grade III (musculotendinous disruption) that requires complete withdrawal from climbing and a longer period of physiotherapy.

How To Reduce Your Risk of a Lumbrical Injury?

Careful long-term training of one-finger grips, as well as proper pre-climbing warm up, will reduce injury risk. Lumbrical muscle training techniques will be covered in an upcoming T4C video, but cautious less-than-body weight fingerboard training on a deep, comfortable mono pocket is a good place to start (after a thorough warm up, of course). Progress to body weight and eventually greater-than-body weight hangs over many months and years. Keep the training volume low and reduce (or cease) training if you experience any pain. A few mono hangs, as part of your larger twice-weekly fingerboard training, along with frequent stretching of each individual finger in the extended position will go a long way toward reducing your injury risk.

What If You Suspect a Lumbrical Strain or Tear?

What should you do if you experience acute or persistent pain in the palm of your hand? Stop climbing, and see a sports medicine doctor or physiotherapist! The video below provides a nice primer on the diagnoses and treatment of lumbrical injury, by Drs. Lutter and Bayer of Sportsmedicine Bamberg (Germany). The English subtitles are a bit hard to read, but the content is excellent…thus, making this a must-watch video for every coach, hard-pulling climber, and sports medicine professional.

References:

- Lumbrical muscle tear: clinical presentation, imaging findings and outcome. Journal of Hand Surgery. Christoph Lutter, Andreas Schweizer, Volker Schöffl, Frank Römer, Thomas Bayer. Published: March 2018.

- One Move Too Many: Understanding the injuries and overuse syndromes of rock climbing. Sharp End Publishing. 2016.

Copyright © 2000–2018 Eric J. Hörst | All Rights Reserved.