The best training for climbing is, well, climbing. Too much of anything else, and you’ll likely find yourself struggling to keep up with your goals. To that end, stay on track with your training via the SAID Principle.

(This article was originally published in October of 2019, but the SAID Principle still applies today.)

In working with hundreds of climbers over the years, I’ve noticed a trend: climbers pouring a significant amount of training time into activities and exercises that are not al that relevant to climbing.

Popular activities like CrossFit, trail running, cycling, weight lifting, and yoga, for example, can consume a tremendous amount of time. Those activities often translate to less time and energy available for bouldering, hangboarding, technical skill practice, and other forms of climbing-specific training. So, is all this time spent on “cross-training” actually time well spent?

While it’s important to live a well-rounded life, complete with plenty of non-climbing pursuits, serious climbers must also resist the urge to go on frequent training tangents. This often means reducing time spent on “junk training”. No amount of CrossFit, yoga, or running will advance your climbing as much as climbing-specific activities.

Effective Training in Accordance to the “SAID Principle”

The SAID Principle (Specific Adaptation to Imposed Demands) states that a specific exercise or type of training will produce adaptations specific to the activity performed, and only in the muscles (and energy systems) that are stressed by that activity.

For example, running produces favorable aerobic energy system adaptations in the leg muscles and the cardiovascular system. However, the muscles and systems not stressed by running undergo no adaptation. Even heroic amounts of running will produce no adaptations in the climbing-specific muscles of the upper-body. Some adaptations from frequent long-distance running will transfer somewhat to stamina-based climbing activities such as multi-pitch, big wall, and alpine climbing. Running experience may also help accelerate recovery between sport climbs. So, with that in mind, there is some benefit to building cardiovascular endurance beyond the realm of climbing. The takeaway here is for climbers to find the most effective dose of cardiovascular training that doesn’t steal too much of their time and energy from climbing.

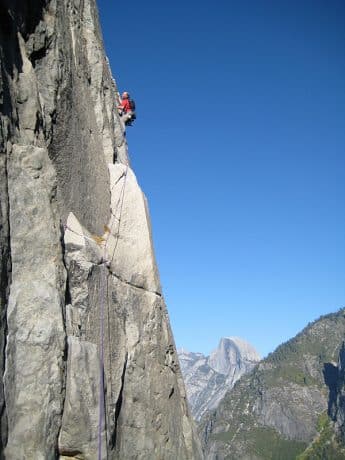

To excel at alpine climbing, dedicate yourself to the alpine. According to the SAID Principle, nothing else will apply quite so directly.

Match Training to Your Climbing Preference

Your body adapts to the specific demands you place on it while climbing. If you boulder a lot, for example, you’ll accumulate the specific skills, strengths, and power demands involved in bouldering. Alternatively, if you climb mostly single-pitch sport routes, you’ll build the ability to zip up 30 meters of rock with relative ease. If you primarily climb multi-pitch routes or big walls, your body will adapt in accordance to the demands of these longer climbs. Or, if your outings are more alpine in nature, your physiological response will harken back to the niche experience of navigating the mountains.

The key distinction here is that while all these activities fall under the category of “climbing,” they each involve unique demands that lead to specific physical adaptations. In that light, the training effect from bouldering will do very little to enhance your physical ability for alpine climbing.

As shown in the table below, all climbing falls on a spectrum. The closer two types of climbing lie on the spectrum, the more the demands of each will carry over.to the other. You can see that sport climbing and bouldering, for instance, lie right next to one another on the spectrum. This means that the specific demands of sport climbing are much closer to those of bouldering. Consequently, the adaptations incurred from bouldering will carry over pretty effectively to sport climbing and vice versa. Bouldering and mountaineering, on the other hand, lie on opposite ends of the spectrum. Those two skillsets don’t have much in common at all.

| Continuum of Climbing Categories | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bouldering | Sport Climbing |

Multipitch Climbing |

Big Wall Climbing |

Alpine/ Mountaineering |

Stay On Mission!

The bottom line: the SAID Principle communicates that effective training for climbing must target your body in ways that matter for climbing. Think about the body positions, technical skills, muscles, and energy systems required for your style of climbing. In accordance with the SAID principle, you should invest over half your total training time in the type of climbing most applicable to your goals in that arena. It’s no fluke that the best boulderers in the world rarely tie into a rope. Likewise, the best alpine climbers have no business on single-pitch sport routes. Tailoring your training to the specific demands and energy systems of your preferred form of climbing is the essence of the SAID Principle. You can even take this one step further by basing your training around specific routes.

In the end, climbers have a philosophical choice to make: specialize and excel in one category of climbing, or become a moderately successful all-around climber. There’s no right answer here. But climbers owe it to themselves to understand the trade-offs.

Related Articles:

- Energy System Training: The Art of the Science

- Three Tips for Off-the-Wall Cross-Training

- Recharge You Climbing Batteries for Energy and Improvement

- How to Develop Strong, Healthier Fingers and Tendons for Climbing

- Will Cardio Help Your Climbing?

Copyright © 2000–2023 Eric J. Hörst | All Rights Reserved.