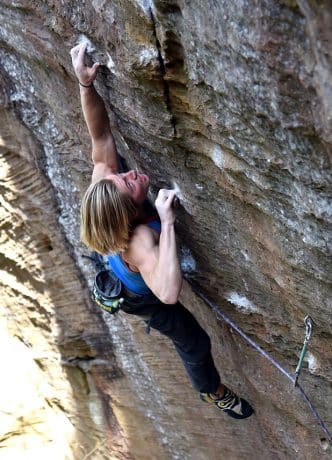

Cameron Hörst climbing Thanatopsis (8c/5.14a/b) at the Red River Gorge, KY. As a two-sport athlete, Cameron (age 16) takes a four-month break from climbing each autumn to play on his high school (American) football team.

Young climbers often bring more excitement to the table than their developing bodies can handle. Help them climb smart and healthy with these eight tips for reducing the risk of one of the most devastating injuries among youth climbers: growth plate fractures.

(This article was originally published in December of 2019, but the risk for growth plate fractures among youth has only increased with the rise of competition climbing.)

Rock climbing is a powerful sport for young minds and bodies. Recreating in the vertical world develops a wide range of important mental skills. It also offers a comprehensive physical workout that builds strength, power, endurance, and flexibility.

What’s more, climbing shapes the character. It imparts important lessons in goal setting, perseverance, challenging fear, and the power of will. Climbing can also last for life. Whereas many other youth sports end at graduation, climbing can continue to be enjoyed throughout your adult life. You can trust coach Hörst on this one—I began climbing at age 13 and I’m still loving the sport at age 59!

Growth Plate Fractures

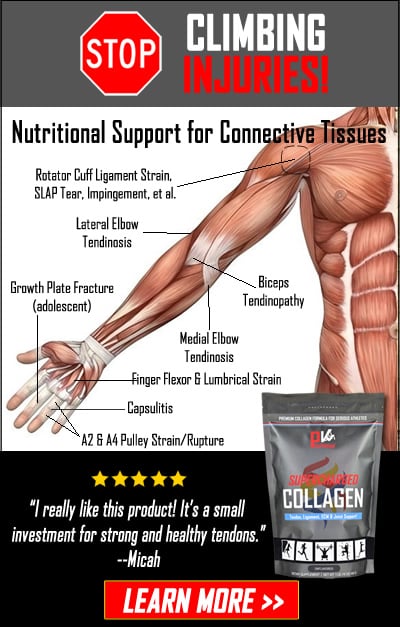

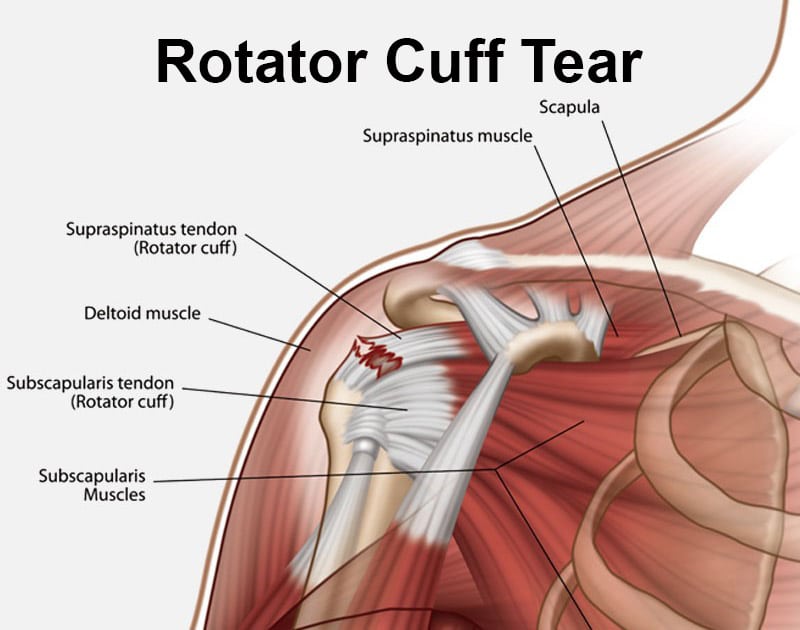

As with any rigorous sport, however, rock climbing presents some physical risks. While the indoor climbing activities that most youths participate in are extraordinarily safe given proper instruction and adult supervision, there is a growing incidence of epiphyseal fractures (a.k.a. injury to the growth plate in the finger) among adolescents to worry about. An increase in hard bouldering, competition climbing, and year-round training have contributed to an alarming escalation in growth plate fractures throughout the youth climbing community. My colleague Dr. Volker Schöffl has been studying climbing injuries for 20 years. In that time, he’s documented a 600 percent increase in epiphyseal fractures over the past decade.

Early identification of this often insidious injury, followed by a relatively short layoff from climbing for a few months usually leads to a rapid resolution. Left to their own devices, however, many youths will continue to climb despite ongoing finger pain. It’s therefore essential that a coach or parent lead the climber in a reduction in—or complete withdraw from—climbing until the pain subsides. Consulting an orthopedist is also prudent, as a simple Hand X-Ray will reveal the extent of the injury. Sadly, many parents and coaches remain ignorant of the risks here. There are even a few coaches who deny that this injury is even “real”, perhaps to allow for their continued use of inappropriate training tactics along the way to building the next champion.

How Does This Injury Present?

Epiphyseal fractures typically occur during the adolescent growth spurt, between the ages of 10 – 14 for girls and 12 – 16 for boys. They’re most common during the year or two of highest growth velocity. Common growth plate injuries in other sports include Sever’s Heel and Osgood-Schlatter’s among running athletes and Little Leaguer’s Elbow with throwing athletes.

Among climbers, the most common site of injury is the middle joint of the middle finger. While a low-grade injury will present as slight knuckle pain only while climbing, a worsening condition will yield more acute pain while climbing as well as discomfort and aching during everyday activities. Since an epiphyseal finger injury usually develops gradually, early identification and reduction or elimination of climbing time will often result in healing over the next few months. Attempting to “climb through it”, though, may result in a Salter-Harris fracture that can take many months to resolve. In severe or untreated cases, you could be looking at permanent disfigurement or dysfunction. A surprising number of the world’s top youth climbers—many who have stood on podiums and pushed the boundaries of outdoor climbing—have suffered a Salter-Harris fracture. Sadly, a few individuals have experienced repeated fractures and been forced to withdraw from the sport for years on end.

How Should Youth Climbers Be Monitored To Reduce Risk of Growth Plate Fractures?

Proactive coaching is essential for enthusiastic youth climbers entering their growth spurt years. Since every child hits their growth spurt at a somewhat different time (some “bloom” early, while others have a delayed growth spurt), I recommend taking a quarterly measurement of height and weight from the age of 9 to 16. Plotting this data quarter-after-quarter will often reveal the onset of increasing growth velocity. This marks the beginning of the 12 to 24 months during which youths are at the highest risk of epiphyseal fracture. This period of time should prompt a coach to more closely monitor the youth’s fingers (such as frequently asking “do you have any finger pain or discomfort?” throughout training) and consider limiting high-intensity finger training protocols.

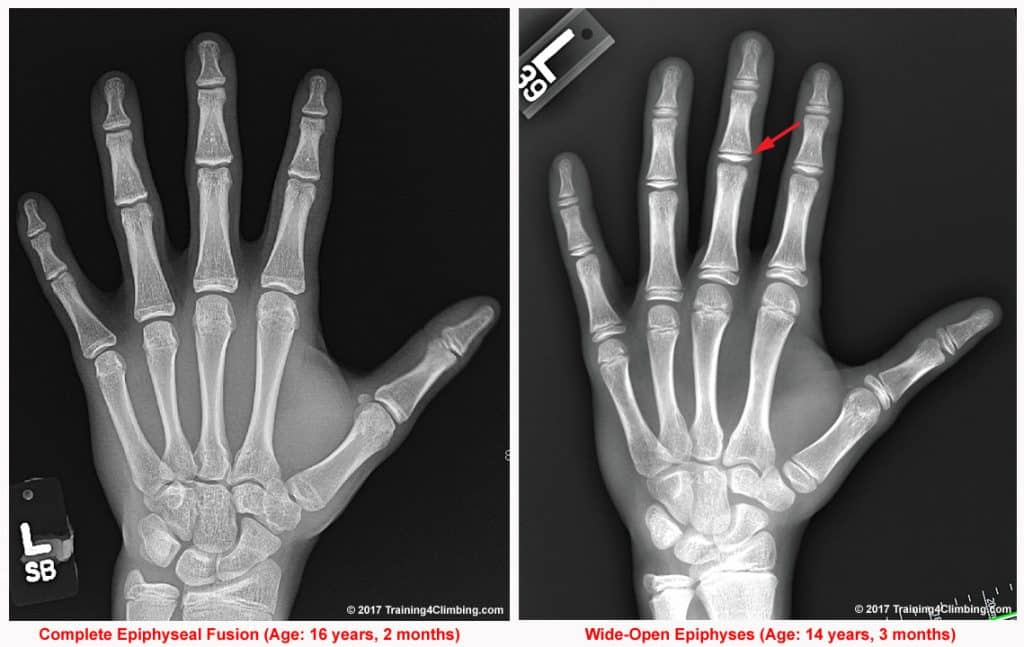

An annual hand ultrasound can also serve as a powerful monitoring tool, even with asymptomatic youths. An X-Ray is appropriate in the case of acute finger pain to determine if there’s a Salter-Harris fracture, and to confirm complete growth plate fusion of a mature youth around age 16. This is an approach I’ve used to keep an eye on the hands of my own sons. An X-Ray on the hand of my older son, Cameron, revealed that his growth plates reached full fusion at age 16 (photo below). I knew then that he’d matured beyond the age of concern for this injury. At that point, I could give him the “all clear” to ramp up his training intensity and volume to elite levels after several years of holding him back from certain advanced training practices.

Conversely, when my younger son Jonathan was 14, his X-Ray revealed wide-open growth plates that placed him smack in the middle of his highest risk period for growth plate injury. By moderating Jonathan’s training, limiting his time doing extreme bouldering, and ensuring he got plenty of sleep and high-quality nutrition, we were able to navigate Jonathan’s growth spurt years without injury while still enabling him to climb at an elite level at the crags. (Read more about the Hörst brothers and how they achieved the 5.14a/8b+ grade by age 11!)

X-rays of two asymptomatic, healthy youth climbers. Note the closed growth plates (left) and wide-open epiphyses of a rapidly growing boy (right). Click image to view full size.

Route climbing tends to be more forgiving on the fingers compared to limit bouldering on small crimpy holds.

8 Coaching Tips for Reducing the Risk of Growth Plate Fractures

- Track a climber’s height and weight from age 9 to 16 to identify the period of highest growth velocity (when the injury is most common). Consider an annual hand ultrasound (or X-Ray in the case of acute pain) to screen for injury and to identify when the growth plates fuse (the end of GP injury concern). Coach each youth climber as a unique individual; a “slow grower” may be less at risk of growth plate injury than a fast-growing climber of similar ability and exposure.

- Coach a comprehensive approach to improving climbing performance, with a strong emphasis on technique and mental skill development, rather than placing excessive focus on physical training.

- Avoid specialization (such as a singular focus on extreme bouldering) and foster the development of diverse climbing skills by exposing youths to many different styles of climbing. Place value on onsight, flash, and “second go” climbing over projecting limit boulders and routes.

- Favor generalized training with young climbers, including the development of antagonist and stabilizer muscle, aerobic capacity, flexibility, and tumbling ability. Keep training fun and varied, rather than regimented and highly targeted. Utilize a wide range of body-weight exercises (such as pull-ups, push-ups, core exercises, etc.) prior to the growth spurt, and introduce a limited number of free weight exercises and a modest amount of climbing-specific training during the growth spurt years.

- While highly fit and advanced youth climbers may be able to do a small amount of hangboard training and “laddering” up a campus board, they should not engage in any “double dyno” campus training nor weighted hangboard training during their growth spurt years. The most prudent coaches will allow no campus board training during the growth spurt years.

- During the period of highest growth velocity, time spent on “limit bouldering” should be reduced to just 30 to 60 minutes once or twice per week. Climbing frequency should be limited to 2 to 4 days per week during the growth spurt years, with an immediate reduction in climbing time at the first sign of pain in the knuckles.

- Coaches should emphasize minimal use of the crimp grip, which is highly stressful on the middle (PIP) joint of the long fingers. Route setters should avoid setting excessively crimpy problems for youth climbers.

- All youth climbers should have an “off-season” during which they do little or no climbing for one to four months. Playing a second sport is strongly recommended through age 16, in order to develop a high physical IQ and diverse motor skills that will last a lifetime.

Related Articles:

- Youth Climbing Injuries and Prevention

- Age-Appropriate Strength Training for Youth Climbers

- Cognitive Development for Youth Climbers

- Skill Development for Youth Climbers

- Overview of Youth Training for Climbing

Copyright © 2000–2023 Eric J. Hörst | All Rights Reserved.