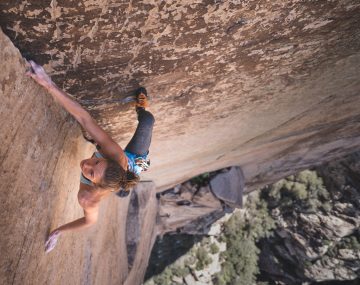

If there’s one guarantee in sports, it’s that injuries will come for us all at some point. Pro climber Amity Warme has approached the recovery process from a full pulley rupture with the same strength and grace that she brings to her climbing—and that’s what separates athletes who last from those who fade away.

Aside from Tommy Caldwell’s infamous run-in with a power saw, Amity Warme may have the best finger injury story in climbing history. Just like Caldwell, Warme’s accident had nothing to do with climbing itself. She sliced her middle finger with a sharp kitchen knife while preparing food, cutting deep enough to partially lacerate her A2 pulley.

But she didn’t know that at the time. “We thought I’d only nicked the tendon sheath,” she explains, “and that climbing on it would be painful, sure, but would not make the injury worse. I had a big objective and film project lined up on El Cap: free climbing El Niño (5.13c), so I put my head down and pushed through the (extreme) pain.”

Warme ultimately made the educated decision to persist with her attempt on El Niño based on what she knew of the situation. In the end, her finger survived the siege—but only just barely.

Amity Warme had the mental strength to climb through a full pulley rupture without realizing it—and to hold herself back enough to recover.

Climbing El Niño With a Ruptured Pulley

Once on the route, Warme noticed a few new sensations in her finger that she’d only recognize in retrospect as warning signs of the injury regressing. “While working the technical, crimpy 5.13 pitches down low on the route,” reflects Warme, “I felt my finger pop a couple of times but disregarded it, not realizing that these pops were my pulley rupturing the rest of the way. I continued to forge ahead with my climbing plans, not knowing whatsoever that I was climbing through a fully ruptured A2 pulley on my left middle finger.”

If Warme had known better, she likely would have made the difficult, but smart, choice to back off of El Niño and sacrifice that goal in the short-term in the name of her long-term health and climbing performance. But once the pulley had fully ruptured, Warme actually noticed a decrease in pain compared to when it was only partially ruptured. That led her to believe that the injury was improving. Yet again, Warme made what she truly thought was an educated decision to keep climbing.

Warme and her climbing partner, Brent Barghahn, successfully sent El Niño in early November. They took the Pineapple Express variation, which allowed them to climb all 25 pitches of the 5.13c route free. That’s impressive enough in isolation. When you consider the fact that Warme managed the feat without the help of a functioning A2 pulley, it becomes even more so.

None of this is to say that it’s a good idea to climb on an injury, especially one as severe as Warme’s. But it does demonstrate the strength of her character. It’s a testament to Warme’s stubborn—er, determined—attitude toward her climbing goals. She doesn’t make a habit of knowingly making decisions that will hurt more than help in the long run. When Warme believes that she can do something without putting herself at risk, though, you’d better believe that she’ll summon all the strength it takes to see it through.

The Aftermath of El Niño

By the time they returned to the ground, it became clear to Warme that something about her initial interpretation of the injury was off. After a few days of reduced pain right after the full rupture, her finger became more swollen and sore than ever. She even took two rounds of antibiotics in case she was dealing with an infection. It was only when Warme returned home to Colorado and could take advantage of her health insurance that she could get imaging that revealed the true nature of her injury.

The images revealed that not only did Warme suffer a full rupture of her A2 pulley, but the pulley had also gotten lodged underneath the tendon to create what’s called a “FLIP complication”. In many cases, this condition requires surgery to realign the pulley so it can heal properly. Warme and her team of medical professionals, including some of the country’s best climbing-specific physical therapists, decided to hold off on taking the surgical route right away and see if the pulley would take well to traditional methods of treatment for a full rupture. It would still take plenty of time and patience on Warme’s part, but with far less invasive measures involved.

Pulley Splints for Pulley Rupture Recovery

Since then, Warme has taken an aggressive approach to rehab that’s gotten her back to work on the wall with minimal downtime. The doctors and physical therapists that she consulted weren’t sure if the FLIP complication meant that Warme would need surgery or if the pulley would heal like any other rupture. She and her team opted to try the normal rehab routine for Grade III pulley injuries before going the much more invasive surgical route that would extend her recovery time.

That involved wearing a pulley splint at all times in combination with progressive loading. Pulley protection splints help with recovery by aligning the pulley with the bone. This alignment allows the pulley to return to its proper placement while reducing stress on the pulley itself while it heals. Pulley splints also provide more compression and rigidity than typical taping methods. Research on the protocol demonstrates that 90% of climbers wearing pulley splints post-injury made a full recovery within eight months.

Her father, Winston Warme, has also developed another version of the pulley splint in his work as an orthopedic surgeon: the S.P.Ort. Warme has used both the original pulley protection splint and the S.P.Ort during her rehab process. “Since I’ve been having to wear a splint 24/7,” she says, “I’ve found it really nice to be able to alternate between these two to help spread out the wear and tear on the skin in that area.”

The S.P.Ort Splint Warme has been wearing throughout her pulley rupture recovery process.

Physical Therapy for Pulley Rupture Recovery

A few weeks of rest gave Warme’s finger the chance to shake the inflammation that had only worsened during her time on El Cap. She then began to lightly load the finger in an open-hand grip position. “This puts much less strain on the pulley than a crimp grip,” Warme clarifies, “but allows the tendon to maintain strength while it’s healing.” Loading allows the pulley to regain the specific capabilities required for climbing. Here’s how physical therapist Jared Vagy, a.k.a. The Climbing Doctor, describes the purpose of loading for pulley recovery:

“When tendon and ligamentous tissue heals without a directed load, it lays down a matrix that is disorganized and irregular. When a directed load is applied to the healing tissue, that matrix is reorganized into a structured form that follows the load direction. To visualize the concept, think of this analogy. Imagine you have a bunch of individual strands of string and you’re holding the ends of every string in each hand. Without pulling your hands apart, the strings are bunched up and there is no order to the strings. Now if you pull your hands apart, every string becomes straight and taut, and there is an ordered matrix of consistent fibers. This is what we want for our healing tendons and ligaments. For optimal strength and performance of the tissue, there needs to be an ordered matrix, and to do that we need to apply a therapeutic load while our tissue heals.”

Warme has abided by her rehab routine with the same vigilance and attention to detail that makes her such an accomplished climber. She’s not only incrementally increased the intensity of her loading over a period of weeks, but she’s also incorporated a Tindeq Progressor to precisely quantify the load so she doesn’t risk under- or over-stressing the tissues.

Collagen for Pulley Rupture Recovery

As a registered dietitian, Warme understands the role of nutrition in injury recovery better than anyone. She’s been using PhysiVāntage Supercharged Collagen on top of a well-rounded diet to help reconstruct the connective tissues in her finger.

“All of our connective tissues are made up of collagen,” Warme says, “but the tissue in our tendons and pulleys is much slower to adapt and build strength than something like muscle tissue. It takes diligent effort to build and repair connective tissues. Supplemental collagen is made up of the three amino acids that form the structure of collagen tissue in the body. The idea here is that by increasing the number of these amino acids in the blood and then performing a loading protocol, the tissues under load will act as a sponge and absorb those collagen-specific amino acids, which then helps fortify or repair them.”

Warme takes 15 grams of collagen in the 30-60 minutes before each therapeutic loading session. She emphasizes the timing, because “simply taking collagen at a random time of day is like mailing a letter without an address: it could go anywhere in the world,” she relates. Warme likens the loading protocol to the address on the letter that tells the collagen exactly where in the body to go.

Though Warme admits that “the science is still young” when it comes to the effectiveness of collagen, she’s confident in the copious evidence that exists so far in support of strengthening soft tissue. There’s little to lose and much to gain by including supplemental collagen in your diet.

“The great thing about collagen is that it really has no potentially negative side effects,” declares Warme. “It’s simply amino acids (the building blocks of protein), so it does no harm to you to take it and it is very likely helpful in maintaining healthy tendons and ligaments. So to me, it feels like a no-brainer to use collagen to support my finger rehab. I am grateful that Physivantage creates a quality product that I can use to help support healthy tendons!”

Training in Pulley Rupture Recovery

As of mid-January, about three months after the initial injury, Warme has been cleared to return to climbing. She sticks to doing so “statically, very controlled, well below my limit, and only in an open-hand grip”. That’s easier said than done for such an ambitious athlete. Restraint takes more discipline for Warme than working at maximum capacity.

To stay strong and sane in the meantime, Warme has funneled her focus into general strength training alongside her pulley rehab routine. She knows that the best way to recover in time for her spring and summer climbing goals is to see the protocol through while fortifying her full-body strength. She’s also building mental strength by intentionally focusing on “what I can do versus what I can’t” while injured. By the time her finger is ready to crank, Warme will have recouped enough durability and determination to match her enthusiasm for climbing!

The Takeaway for Injured Athletes

If there’s one thing all ambitious athletes have in common, it’s the pain—physical, mental, and emotional—of wrestling with an injury. None of us are invincible. Each of our bodies will inevitably break down from time to time. Every time an injury sidelines an athlete, it induces real heartbreak because it steals something essential to who we are and how we interact with the world.

Warme is no exception here. But we can all learn from her commitment to do what she can with what she has. On El Cap, that meant pursuing her goal despite the pain because of what she thought she was dealing with. Now, it means leaning into other forms of staying active and treating her body with respect so she can return to full strength as soon as possible. Either way, Warme sets an example worthy of admiration.

Amity Warme takes 15 grams of Supercharged Collagen every day, 30-60 minutes before each rehabilitative finger loading or climbing session. She makes sure to time her dosage precisely because of the research behind how collagen-specific amino acids can be targeted to a specific body part via loading.

Related Articles:

- Fueling for Sending with Amity Warme, Sports Dietitian

- How Jordan Cannon Trained to Send the Trango Tower

- How Natalia Grossman Overcame Mental Barriers for World Cup Wins

- Adrian Vanoni Keeps It Simple to Climb 5.14 Cracks

- Climb More Creatively with Alex Megos’ Stretching Routine

Copyright © 2000–2024 Lucie Hanes & Eric J. Hörst | All Rights Reserved.