(This is a minor update on an article first published here in 2015.)

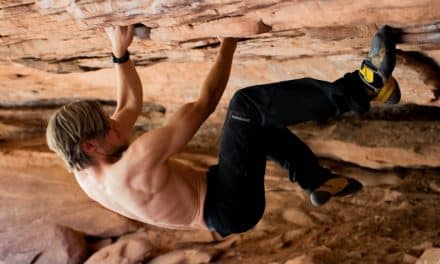

Photo: Alex Megos climbing Wolverine (V14). As a vegan, Alex consumes a daily dose of PhysiVantage Creatine to support his recovery and power. (@dinosaauuur)

Will Creatine Supplementation Enhance Climbing Performance?

Answer: It depends.

To determine whether creatine benefits climbers, we need a highly sport-specific approach.

Many supplements claim to boost strength, power, and muscle growth, but most fall short. However, creatine stands out—it has been proven in numerous well-conducted studies to increase muscular strength. Does that make it a must-have for climbers? Not so fast, my highball-sending, redpoint-crushing friend!

Creatine in Sports—Proven Benefits

Let’s look at the facts. Creatine is the most effective legal sports supplement available. Studies have consistently shown that it enhances explosive strength (Toler 1997 & Kreider 1998). Additionally, high doses increase lean muscle mass, making it a staple for athletes across various disciplines, including football, baseball, weightlifting, bodybuilding, MMA, CrossFit, sprinting, and general fitness.

Creatine is a naturally occurring compound in our bodies, playing a key role in ATP production—the energy source for short, explosive movements—via the anaerobic alactic energy pathway. While present in small amounts in red meat and other animal products, dietary intake is typically limited to just one or two grams per day. Research indicates that supplementing with 20 grams of creatine daily for five to six days—known as “creatine loading”—can enhance short-duration, high-intensity performance, such as sprinting or weightlifting. This makes it a popular choice for athletes seeking increased strength, power, and lean mass.

Notable Side Effects: Weight Gain and Cell Volumization

Two key side effects of creatine loading are weight gain and “cell volumization.” Because creatine is stored in the muscles alongside water (with about 95% of it residing in muscle cells), intracellular water levels increase. During the six-day loading phase, as creatine stores build, more water is drawn into muscle cells, giving them a fuller, pumped appearance—exactly what bodybuilders and fitness buffs desire.

This process typically leads to a gain of one to two pounds (or more) of water weight. While beneficial for athletes in sports where added mass and inertia enhance performance—such as football, baseball, or combat sports—it can be problematic for climbers, where a high strength-to-weight ratio is critical.

Some argue that stronger muscles from creatine supplementation compensate for the added weight. However, creatine doesn’t selectively enhance only the “climbing muscles”—it loads across all muscle groups, with a disproportionate effect on larger muscles like the legs. For climbers, increased lower-body mass is counterproductive, making the standard creatine loading protocol—doses larger than 5 grams per day—less than ideal.

Another concern is the “cell volumization” effect. Bodybuilders appreciate the increased muscle pump that creatine provides, but for climbers, this can lead to faster muscle fatigue. I noticed this firsthand when I experimented with creatine in 1993—it seemed to give my muscles extra “zip,” but I also experienced a quicker pump and premature fatigue.

The likely explanation? Excess intracellular water may accelerate the occlusion of capillary blood flow during strenuous exercise, causing muscles to fatigue faster once the body shifts from the anaerobic alactic energy pathway (after about 10–15 seconds). While creatine might enhance brief, powerful climbing bursts under 15 seconds, it could hinder performance on longer boulder problems and sustained roped ascents.

The Best Strategy for Climbers: Micro-Dosing Creatine

Despite these concerns, I believe that well-timed micro-doses of creatine can benefit climbers by aiding recovery—without the drawbacks of full creatine loading.

The protocol I’ve used for years involves taking 1–2 grams of creatine in a pre-workout drink and another 1–2 grams in a post-workout or bedtime protein shake. This delivers just slightly more than a standard dietary intake of creatine, enhancing recovery between exercises, climbs, and training sessions without excessive water retention or unwanted muscle gain.

For climbers looking to maximize performance without the downsides of full creatine loading, micro-dosing is the way to go.

Download a free Creatine Users Guide for climbers and non-climbing athletes from PhysiVantage.com >>

Key Points:

- Micro-dosing creatine (1–5 grams per day) may provide a slight power boost and aid recovery between strenuous exercises, bouldering, and routes—without significant side effects.

- High-dose creatine loading (10–20+ grams per day) is likely counterproductive for climbers, as it can lead to 1–5 pounds of weight gain and increased muscle pump (especially on long boulders & routes), which may hinder performance on sustained climbs.

- A small percentage of individuals are creatine non-responders, meaning they experience no noticeable effects from supplementation.

- Vegetarian and vegan climbers may benefit more from micro-dosing, as their diets lack natural creatine sources found in meat.

- Some users report cramping, especially in the legs and feet, and long-term high-dose use may pose risks to kidney health.

- Creatine is not banned and is not listed as a prohibited substance by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA).

Copyright © 2015-2025 Eric J. Hörst | All Rights Reserved.