There’s no way to make climbing 100% safe for anyone. But youth climbers face their own set of consequences based on where they are in the growth cycle. Anyone working with youngsters climbers needs to know how to best prevent and care for youth climbing injuries.

(This article was originally published in May, 2015)

Climbing is a wonderful brain-, body-, and character-building sport for kids, but it’s also a sport that presents very real risk of injury. Fortunately, professional instruction/coaching can largely eliminate the risk of serious injuries due to falls or human error. Still, there’s the hidden, more subtle risk of various overuse injury, which is the focus of this article.

Climber Waylon Larson practices good form under coach supervision to prevent injuries.

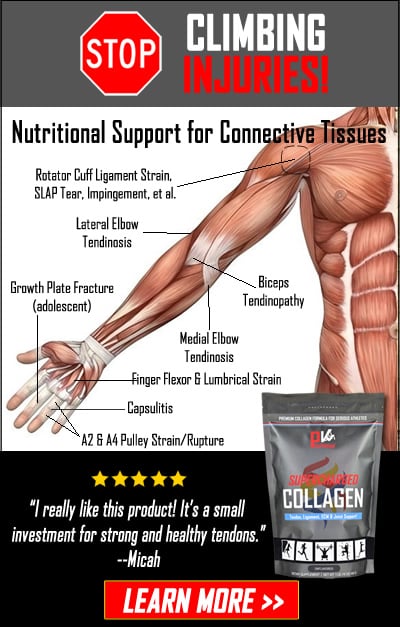

The most common non-impact injuries among teenage climbers are overuse injuries to tendons, joints, and bones of the fingers, including stress fractures and damage to the growth plates. Any youth climber, regardless of age, experiencing chronic pain in the fingers (or elsewhere) should cease climbing for a few weeks and consult a doctor if the pain continues. As a hard-and-fast rule, climbing and climbing-specific training must be limited to an aggregate of four days per week. The guidance of an adult climber or coach is extremely beneficial both in helping structure workouts and in monitoring rest and nutritional habits. Let’s delve deeper into the subject, including important strategies for preventing overuse injuries in youth climbers.

Injuries to the Growth Plates of the Fingers

The most disturbing injury trend among youth climbers is the increase in fractures to epiphyseal (growth) plates of the fingers. Though most often observed in the hardest-training, hardest-climbing youths, all youth climbers should be monitored for the onset of joint pain in the fingers. Growth plate injury often develops over time, first showing up as minor joint swelling and pain while crimping and—if not treated with rest—progressing to acute pain, increased swelling, reduced range of motion, and in the worst cases disfigurement that can become permanent.

Adolescent climbers are most at risk for growth plate fractures during their growth spurt years (ages 11 – 14 in girls, and 12 – 16 in boys), although they can occur up to the age of eighteen prior to complete fusing of the growth plates. European research and anecdotal evidence here in the States reveals that double-dyno campus training is a leading cause of growth plate injuries. However, epiphyseal fractures can also develop in youths who engage in frequent intensive bouldering—the kind involving copious dynamic movements and repeated extreme crimping moves.

Regardless of how the injury develops, complete withdrawal from climbing is essential until pain and swelling subside (typically 2 – 6 months). Resumption of climbing should be gradual, with a primary focus on large-hold bouldering and moderate roped climbing, rather than a quick return to the same program that produced the injury in the first place. Recurrence of finger pain and swelling will require a longer break from climbing—perhaps a full year. Consulting a doctor would be likewise prudent.

Preventing Growth Plate Fractures and Other Injuries

Epiphyseal fracture (non-traumatic stress fracture at the growth plate) is an increasingly common injury among high-end youth climbers, especially those specializing in V-hard bouldering and/or performing dynamic training such as the Campus Board. Photo courtesy of Volker Schöffl.

First and foremost, climbers ages eleven through sixteen should do absolutely no double-dyno campus training. A small amount (a few sets, once or twice per week) of controlled hand-over-hand campus laddering on large holds may be permitted for climbers strong and mature enough to do it with smooth, low-impact movements. Also of high importance, during all practice climbing, is a conscious favoring of the open-handed grip over the crimp grip on all but the smallest holds (which require use of the crimp grip). Finally, youth climbers should do little, if any, hypergravity training—that is, climbing or hangboard training with weight added to the body in the form of a weight vest or belt. Some weighted pull-ups on a bar or bucket hold is okay for older, stronger youths.

Given the immense popularity of bouldering today, many youth climbers come to prefer it over roped climbing. Unfortunately, year-round specialization in bouldering places them in a high-risk group for growth plate fractures, as well as other maladies such as finger-tendon injury, elbow tendinosis, and shoulder injury. A far better approach is for a coach to direct a near-equal focus on roped climbing and bouldering. Roped routes generally have less severe cruxes and fewer dynamic moves, and instead test a climber’s endurance, serial movement skills, and mental abilities. By alternating between roped climbing and bouldering every few weeks or months, risk for youth climbing injuries is reduced, while at the same time climbing skills are expanded thanks to the exposure to a wider range of climbing situations. In terms of climbing frequency, three or four days per week is ideal—anything more vastly increases injury risk, especially in hard-climbing youths.

In a previous article I covered the importance of warm-up exercises and stretching, antagonist-muscle training, and end-of-session or nighttime flexibility training. Disciplined follow-through in all of these areas will both reduce climbers’ injury risk and enhance on-the-rock performance.

Proper nutrition and adequate sleep are the other side of the coin when it comes to preventing youth climbing injuries. Calorie restriction is inappropriate in almost all situations for adolescents, although some restriction in the consumption of unhealthy junk and fast foods can be beneficial and is certainly wise. Youth athletes should be encouraged to eat “three squares” a day, including lots of fruits, vegetables, lean meats, and low-fat dairy products. Healthy snacks, such as energy bars, bagels, and even low-fat chocolate milk, are excellent as between-meal and climb-time snacks. In terms of sleep, nine to ten hours per night is best, with eight hours being the bare minimum.

Find the Balance

In closing, perhaps the best way to prevent the various injuries mentioned above, including mental burnout, is for youth climbers to participate in activities and sports outside the climbing world. While an overbearing coach or parent may preach otherwise, young climbers absolutely can come to perform at a national- or even world-class level while at the same time participating in other extracurricular activities.

With proper planning, guidance, and encouragement, youths can become excellent in several life areas and come to enjoy the rich experiences available in both the horizontal and the vertical world. Need proof? Consider sport climbing superstar Sasha DiGuilian. In high school Sasha ran cross country and track, climbed a few evenings per week at the gym, and aced her classes at school—and, oh yeah, upon completing high school she become one of the first women to climb 8c+/9a! Similar, my sons Cameron and Jonathan have both climbed multiple 5.14a/8b+ routes, despite having an annual four-month off-season from climbing so as to play American football each Fall.

Ultimately, it’s through a balanced approach to climbing that today’s youths are most likely to remain healthy, happy, and on a steady, sustainable track to becoming accomplished climbers for life!

Related Articles on Youth Training:

- Overview of Training for Youth Climbers

- Skill Development of Youth Climbers

- Cognitive Development of Youth Climbers

- Age-Appropriate Strength Training for Youth Climbing

Copyright © 2000–2022 Eric J. Hörst | All Rights Reserved.