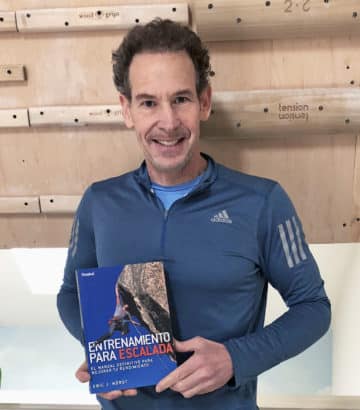

With the recent release of the Spanish edition of Training for Climbing (“Entrenamiento para Escalada“), I was pleased to do a climbing training interview with Desnivel magazine and talk about training past, present, and the future. The full-length interview is available in September/October 2018 issue of Desnivel (#386, as shown below)—if you live in or are visiting Spain, please pick up a copy!

For the benefit of my English-speaking friends, I’ve posted below many of the training-oriented questions. I hope you find it interesting and informative.

The Desnivel Interview:

How has climbing training evolved in the last 20 years?

There has been tremendous progress in coaching of movement skills, especially given the increasing access of indoor climbing walls and growing number of sport climbing areas around the world. Climbers can now more easily practice their skills on the wall, whereas 20 years ago many climbers didn’t have nearby access to climbing gyms or sport crags…and so back then training was very limited to basic strength and power exercises. I believe today’s climbers, with easier access to indoor walls, are much more technically advanced and skilled at moving over stone very effectively and efficiently.

In terms of state-of-the-art physical training, however, I do not believe there’s been much innovation or advancement in the last 20+ years—after all, the two primary training platforms (hangboard and campus board) have been used by top climbers since the late 1980s. What new revolutionary training has been developed since then? Not a whole lot. Although I must mention one useful innovation, catching on in the past decade, is the Treadwall—a superb training tool, especially given use of specific interval training protocols.

One positive trend in recent years is improved coaching and increasing availability to information on how to train more effectively on a campus board and hangboard. Importantly, there’s even some research-based protocols given the work of Eva Lopez and others. So there is some progress, by way of better training programs, on how to train more effectively.

Of course, training videos and articles are ubiquitous on the Internet; however, there seems to be almost as much bad advice out there as there is good advice…and so it’s difficult for some climbers to make sense of it all and discern how they should best train to improve. Ultimately, I believe a climber must study the material and come to make intelligent training choices based on their unique situation and goals. Naturally, some make unfortunate choices (based on misinformation, old-school dogma, or impulse) and, thus, get poor results and perhaps even injured.

How do you test athletes and assign training programs?

I believe athlete testing is important, especially for higher level climbers pushing their limits or entering into competition. However, testing methods have not been standardized or validated, so different coaches test in different ways…some better and more accurate than others. I believe testing practices will be fine-tuned and agreed upon in the coming years, but until then each coach must use what they find most practical and effective. A few top coaches will utilize technology for testing of important physical constraints such as climbing-specific maximum finger force, a climbing-specific peak lactate (anaerobic capacity), and a climbing-specific VO2 test…to measure aerobic power level. I hope in 5 years all professional coaches will be doing this type of standardized testing. Accurate athlete testing of key performance indicators is the foundation from which a highly effective training program can be designed and implemented.

Eric Hörst interview in Desnivel (Fall 2018).

What are the common training mistakes among climbers?

I do see many of the same training errors, but they differ depending on the experience/ability of the climber. Many newer climbers focus too much of strength & power training earlier on—this sometimes leads to injury and may stunt technical growth, as less-experienced persons should work mostly to develop climbing movement skills, problem-solving, and other mental skills. Enthusiastic intermediate climbers tend to be gluttons for punishment—sometime doing greater and greater volumes of climbing and training…always thinking that “more is better.” This can lead to injury, frustration, and burn out. So I believe intermediate climbers can benefit greatly from input of a climbing coach to help guide personalized training.

Elite climbers are often very good self-coaches, given they’ve developed a strong intuitive sense of what works for them…based on many years of experience. However, opening up the next grade often demands a more nuanced approach and introduction of some new training elements—either project-specific training or use of novel training strategies to bring about further physiological gains. These are things I’m working on…developing new training protocols and strategies to bring about gains in strength and endurance. For example, proper use of my energy system training conceptual model can open up a new level of training effectiveness for many climbers—there’s a growing knowledge base on this topic, and a good primer on energy system testing and training in latest edition of Training for Climbing. My personal research on this is building each year….which often I share in my monthly podcast (subscribe on iTunes to Eric Horst’s Training for Climbing podcast).

Is planning essential to improve climbing level?

Yes, a serious climber needs a daily/weekly training plan to make gains while still having enough time to recover and, hopefully, also climb outdoors. Also, an ambitious climber needs a long-term plan…which begins with knowing the big picture of their goals in the next year or two (or more). Again, a coach can be very helpful—both in terms of developing daily training schedule but also helping shape the climber’s long-term actions and helping integrate them with other important life aspects (school, work, family, etc).

Your sons are great climbers who did 8b+ at a young age. Now there are many children going to climbing classes, do you think that in general the coaches are prepared to plan the training of children and young people?

Yes, both of my sons, Cameron (now age 17) and Jonathan (now age 15) climbed 8b+ at age 11, and this despite only climbing a few days per week and NOT climbing year-round. As a coach and parent, I’m against single-sport specialization until after puberty, since the growing brain and body is nourished by learning novel movement patterns and mental skills acquired via a variety of sports and activities. This approach develops a higher “physical IQ” and a solid, balanced body that will hold up to the rigors of climbing (and life!) as an adult. And so I encouraged my sons to try many sports growing up…and even now they continue to enjoy playing America football each Autumn. Since they do not climb year round, this approach may be holding them back a bit (in climbing grade)…but the long-term payoffs will be a fitter mind and body, avoid burning out on climbing as a teenager, and perhaps set them up to really excel at climbing (if they choose to be pro climbers) when they are adults. We’ll see—that’s their story to write!

Mental training is, of course, very important—I even wrote a powerful book on this called Maximum Climbing! The problem is that mental training is more nebulous than physical training—it’s often about making the right choices, holding the right concepts in mind, breaking bad habits and various forms of self-sabotage, controlling energy level and mental state, and becoming self-aware of your thoughts and whether the thoughts are helping or hurting you. These are difficult things for some people to grasp because their mind has been running wild and free for so long. Certainly the best climbers eventually learn to take firm control of their thinking…and come to exhibit incredible mental strength. I believe that physically strong climbers like Adam Ondra and Alex Megos possess even stronger minds—imagine that!

As for percentages of mental vs. physical training…that’s hard to say. Physical training is done a few hours per day, whereas a serious climber needs to properly direct their thoughts throughout every day (even rest days) to stay on mission and avoid counterproductive behaviors that will hold them back. Again, it’s about seeing the big picture of your goals and knowing each day what to do to advance toward those goals.

In terms of nutrition…are there many false myths?

Nutrition is a complex topic with individual differences—though not well recognized, genetics play an important role in how certain foods effect a person’s mood, strength, recovery, and health. There are indeed some fad diets and food “myths” that I occasionally hear from climbers…that may not help them and might even slow recovery and training results. Muscles and tendons require specific nutrients, and so proper nutrition plays a role in proper recovery and reducing injury risk.

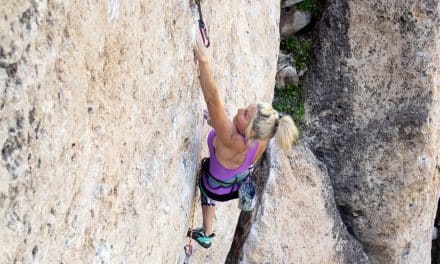

With indoor climbing we are seeing many new movements…closer to parkour than climbing. Does this cause a change in the usual patterns of training?

Certainly for competition climbers, there’s a need to broaden out the climbing skill set to include elements of parkour and gymnastics. It seems the difference between indoor bouldering competitions and outdoor climbing is increasing, so naturally the training must be modified to accommodate this—the extreme body positions and use of dynamics and momentum now common to elite indoor bouldering competitions. However, the majority of climbers do not do competitions, and so for the average climber indoor climbing is a means to the ends of climbing outdoors. Therefore doing parkour training, for example, will not likely improve one’s outdoor climbing.

Do you have a training center in your own home? Do you do family training?

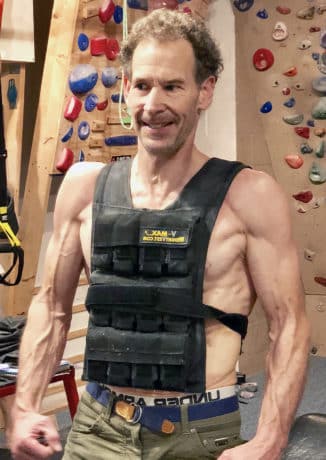

We do have a large at-home training set up…including a bouldering wall with several different angles, a campus board, system wall, something like 12+ hangboards, and a Treadwall, Endless Rope machine, gymnastics rings, free weights, a rowing machine, and more! We can train here effectively as a family and I occasionally have pro climbers visit for testing and training guidance. Of course, I experiment a lot with new training protocols and pilot research projects I’m working on. I have the research grade tools to do precise grip force and lactate testing, among other things. It’s very efficient to have this all available in my house, especially given the busy lives of my family members—we can easily engage in training at different times of day with no travel time to a gym.

What advice would you give someone who decides to start training for climbing?

If you are new to climbing (<2 years), get quality instruction and strive to become a master of many different climbing techniques…and don’t obsess on strength training just yet! As you approach the 7th grade (5.12a), however, it’s important to begin some basic strength and power training, as well as do some regular antagonist muscle training. Developing muscle balance and stable/functional joints is important for injury prevention as you advance into the higher grades. As you approach the 8th grade, I recommend consulting a coach for testing (to identify personal weaknesses)…and to acquire a personalized higher-intensity training program that will put you on a trajectory toward your climbing goals.

Finally, could you describe your beginnings as a climber and your history as an author and coach?

I’m nearly a life-long climber (41 years on the rock and counting!), a climbing coach of 30+ years, a researcher, industry consultant, and author of eight books with many foreign translations.

My older brother introduced me to climbing in 1977 (when I was 13 years old). Growing up in the northeastern United States we climbing mostly at the Shawangunks, Seneca Rocks, and in the White Mountains of New Hampshire…but also did summer trips to the Rocky Mountains of Colorado and Wyoming. Of course, this was all traditional climbing as there were no sport climbs in the USA back in the 1970s into the early 1980s. Then, in 1984 -1986, I begin to bolt some of the first sport climbs (up to 7c) in the United States at Bellefonte Quarry (located in Pennsylvania) and then in 1987 I was one of the leading developers of sport climbs at the New River Gorge…and I did the FA of the first 5.13a/7c+ there in 1987, a route called Diamond Life. I continued to develop many new routes from 1987 to present day with over 400 first ascents to my credit in the USA. Of course, through this period I was also researching, developing, and writing about training for climbing with my first book, Flash Training, published in 1994. I followed this with How To Climb 5.12 (in 1997), Training for Climbing (in 2003), and Maximum Climbing (in 2009). I’ve written two major updates to Training for Climbing, with the latest edition being published in 2017 edition.

Finally, I’m proud to be an ambassador and consultant for several excellent climbing brands including La Sportiva, DMM Climbing, Maxim Ropes, Organic Climbing, and Friction Labs. In January 2019, Eric launched his new brand PhysiVāntage—performance nutrition for climbers. Learn more at PhysiVantage.com.

Copyright © 2000–2018 Eric J. Hörst | All Rights Reserved.