Strength-to-weight ratios are key performance indicators for climbers. Learn one way to increase this ratio via optimizing body composition.

(This article was originally published in September of 2019, and has been updated to offer relevant and realistic recommendations for healthy approaches to body composition changes.)

Strength-to-weight and power-to-weight ratios are important key performance indicators (a.k.a. KPI’s) for climbers. While improving your technical and mental skills is always paramount, training to increase your strength and power metrics is just as essential for reaching the higher grades. Consider that elite climbers, at the ~5.14b/8c/V13 level or harder, typically produce a force from their first finger pad that’s equal to or greater than their body weight. (How does your grip strength-to-weight ratio compare?)

A well-designed training program, then, should produce measurable increases in finger strength and pulling power with little to no weight gain to counteract it. This improves your strength-to-weight ratio by focusing on the strength component. This is the smartest method of improving that ratio for those already maintaining a healthy weight. If you’re carrying around excess body fat, then incorporating some weight loss is likely the quickest pathway to a higher strength-to-weight ratio.

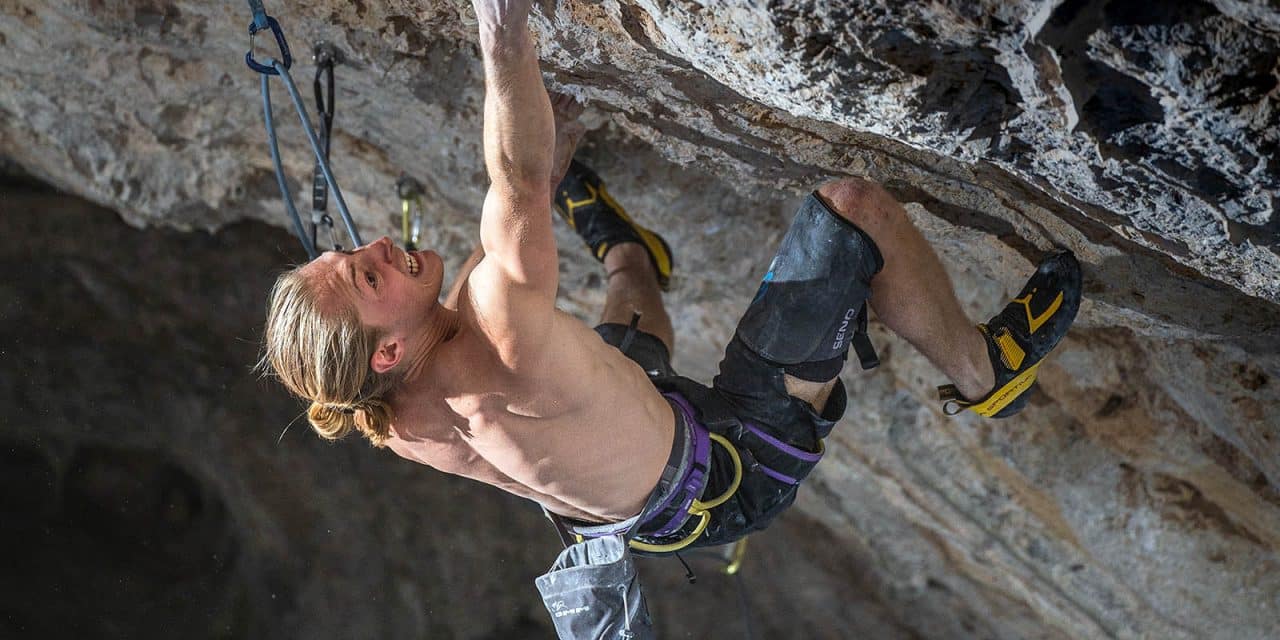

A high strength-to-weight ratio is essential for steep elite-level sport climbs. (JP Melville photo of Cameron Hörst climbing 5.14d)

What’s a Healthy Bodyweight?

As a veteran coach, having worked with hundreds of climbers over the past 30+ years, I believe that the most reasonable body fat percentage for peak climbing performance ranges from 6 to 12 percent for men and 10 to 18 percent for women. Many elite climbers are near the low end of these ranges. Maintaining such a body fat percentage (which is in line with elite athletes in other power-to-weight ratio sports like gymnastics, jumping, rowing, sprinting, distance running), requires an educated approach to eating such that adequate nutrients are present for optimal health and performance.

[NOTE: This article is written with the context of an elite-level climber, not a recreational climber. Of course, a high strength-to-weight ratio makes a difference at all levels of climbing, but it’s a far more critical metric for elite climbers. If you’re a recreational climber, focus on building strength and skill first.]

If you’re not sure how you measure up, consider having your body fat tested via a DEXA scan. Alternatively, a simple skinfold caliper calculation will give you a good estimate. Or you can use the economic pinch-an-inch method on your waistline; if you can pinch an inch, then you are certainly not in the optimal range.

It’s not all about body fat, either. Excessive muscular weight can have just as much of an effect for climbers. In fact, since muscle weighs more than fat per unit volume, large muscles in the wrong place are worse than excess fat. Your previous sports background and former methods of training, as well as genetics, play a large role in the amount of muscle mass you are carrying. For example, perhaps you used to be involved in bodybuilding or a CrossFit, which involve many sets of high rep exercises for the sake of growing larger muscles. Or maybe you come from a family of endomorphs who naturally have larger bones and thicker legs. Regardless of your situation, you can certainly still improve your body composition and strength ratios—but there will obviously be genetic limitations.

Nutritional Strategy

No matter if you can “pinch an inch” or possess large muscles that you’d like to shrink a bit, you can go about strategic body composition changes via nutritional and/or training interventions. Dietarily, aim to reduce “empty calories” from nutritionally negligible foods that don’t add much value to your diet. Think foods that consist of mainly added sugars or saturated fats. Of course, there’s room for all foods in a healthy diet. Just focus on a steady consumption of protein alongside a moderate consumption of carbohydrates the majority of the time.

Getting into specific foods to eat or avoid is beyond the scope of this article. It’s also highly specific to the individual. But the ideal macronutrient caloric breakdown for an athlete is ~60 to 65 percent carbohydrate, ~20 percent protein, and ~15 to 20 percent fat. Fad low-carb/high-fat diets, while often successful at yielding weight loss in the short-term, are generally not ideal for most athletes who need copious carbohydrates to fuel their activity.

Then there’s the age-old question: How many calories do you need, and how much should you reduce calories for weight loss? The truth is, everyone is different. Age, metabolism, insulin sensitivity, activity level, and more can all cause this number to vary drastically from one person to the next. There’s no way to predict exactly what your body needs on a daily basis without experimenting for yourself.

A good place to start is by taking inventory of your regular eating habits. Use a nutrition tracker to get an estimate of your typical caloric intake on different kinds of training days. Then, aim to reduce that number by 250-500 calories. Resist the urge to slash your caloric intake even more than this. You’re still an athlete with high energy needs. It’s not worth sacrificing your performance and overall health for drastic weight loss measures (that often backfire anyway—deprivation isn’t sustainable!)

Training Strategy

In addition to your climbing-specific training activities, you’ll likely need to fall in love with, er, commit to some running in order to change your body composition. It’s one of the most effective methods of incinerating excess fat and shrinking unwanted muscle. Don’t worry about losing your climbing muscles; they’ll stick around as long as you continue to climb regularly and consume 1.2 – 1.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day. Swimming or fast hiking are good alternatives if you can’t run.

Fall in love with running to make effective changes to body composition.

How should you run? There are two approaches I recommend: long-slow distance running and high-intensity interval training.

- Long-distance running is most common for weight loss purposes, as many people believe it’s the best way to burn fat. Sure, going for a 20- to 60-minute run will burn a good number of calories. Doing so a few days per week will likely yield decent result over time. However, focusing solely on long-distance running won’t do much for your metabolism. Excessive distance will also likely detract from your climbing strength and power. If you opt for this form of running, I suggest you limit yourself to three or four 20- to 30-minute runs per week.

- High-intensity intervals (HIT) make an effective companion to long-distance running. I recommend that most of my client athletes do two HIT sessions per week (often alongside long-distance runs). The time investment is just 20 minutes, three days per week, but the metabolic results are better than only churning out more miles at a slower sustained pace. Jog for about five minutes as a warm-up, then alternate between one minute of high intensity running (90% of all-out speed) with one minute of low intensity jogging or walking. Perform five to eight of these intervals, then finish with a couple minutes of cool-down jogging or walking.

As you near your weight target, you can reduce these workouts to just one or two per week alongside your climbing. Just remember that long-term discipline with your diet and climbing-specific training are essential for maximizing and maintaining your ideal strength-to-weight ratio.

Related Articles:

- Fueling for Sending with Amity Warme, Climbing Dietitian

- Performance Nutrition Through the Lens of Top Pro Climbers

- Benefits of Supplemental Protein for Climbers

- Overnight Recovery Tactics for Weekend Warriors

- Boulder and Crag Day Nutrition for Peak Performance

Copyright © 2000–2023 Eric J. Hörst | All Rights Reserved.