Just like the bodies of male and female athletes differ, so do their brains. Female athletes can harness their unique psychological characteristics to infuse their performances with mental strength.

Athletes often forget that they’re more than just a bag of bones, muscles, and tissues. Yes, sports are mostly physical. Performing to your potential requires training your body to become stronger, faster, more powerful, and durable enough to withstand the work it takes to accomplish all of that. But if you only consider physical factors, you won’t see nearly as much growth in your athletic abilities as you could.

Physiological development has a psychological component too. In other words: bodies need brains to do their best work.

Emotional regulation, motivation, confidence, and other mental factors play a role in what we’re able to produce physically. This means that physiological differences between athletes aren’t the only explanation for different results. Larger Type II muscle fibers, for example, aren’t the only reason that men tend to prevail over women in terms of power output while women have an edge in endurance. Different sources of motivation between male and female athletes influence these characteristics as well.

Men may have the upper hand when it comes to physiological prowess. Luckily for the ladies, that’s only half the equation. Let’s take a look at what goes on above the neck in men versus women to see how that affects everything that goes on below—and how athletes of both genders can capitalize on the unique ways that their brains work for the sake of achieving peak athletic performance.

Mental Health

It’s not all societal stigma; women really do experience higher rates of mental health concerns than men, especially within the athletic population. One study on a large sample of elite Australian athletes determined that “women athletes reported higher rates of mental health symptoms, and lower rates of mental well-being” in comparison to male athletes. A second study on an even larger sample size of elite French athletes showed that “20.2% of women had at least one psychopathology, against 15.1% in men,” with regard to conditions like anxiety, depression, and eating disorders in particular.

Some may take this information to mean that female athletes are weaker on both a physical and mental front. However, I see it more as a source of validation for women, as well as a word to the wise. We may be more likely to struggle with elements of our mental health, but that’s not a death sentence. In fact, it gives female athletes the opportunity to pay more attention to their mental health in general. Women can leverage their higher likelihood of developing mental health concerns as motivation to practice preventative self-care. Awareness pays off. The devil you know is better than the one you don’t. For the price of a little more effort up front, we’re less likely to be taken by surprise if and when a mental health issue arises.

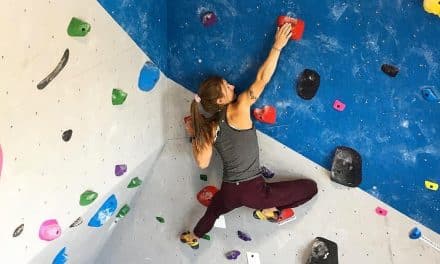

Female athletes can take better care of themselves as athletes and humans by anticipating the mental health challenges that they’re more susceptible to. Photo courtesy of Wieb Ke.

Stress and Emotional Regulation

In the same vein, female athletes tend to experience higher levels of stress. Research on this trend suggests that this stems from a combination of biological and contextual factors. For instance, women experience more stress in general due to chemical differences between the genders, but also because of differences in the way that men and women are supported, respected, and treated as athletes.

There’s a benefit to be found here, though. Female athletes not only experience more stress, but are also more adept at managing that stress. In many cases, this higher level of self-control negates the drawbacks of experiencing more stress in the first place.

The same concept applies to other emotions. A greater range of emotion at higher intensities comes with the ability to exercise more autonomy over those emotions. This propensity for emotional regulation helps female athletes “enter a calmer state of mind more quickly” than male athletes. That’s a handy tool to have at the ready, since nothing ever goes perfectly according to plan—especially in outdoor sports with so many external factors outside of our control. The only guarantee is that there are no guarantees. Good thing we know how to find the calm in the storm.

Motivation

Motivation doesn’t exist in a void. It has to come from somewhere, and the origin matters just as much as motivation itself because when we know where to find it, we can go there to get more of it when we’re running low. Male and female athletes get it from different sources.

While men tend to feel more motivated by competition and the chance to meet their match, women feel more motivated by a sense of competence. The more comfortable we feel doing something, the more motivated we are to do it to the best of our ability. In a study on female athlete motivation, women reported “being motivated by the satisfaction and competence derived from learning new skills and improving their performance” rather than the desire to prove themselves against other athletes.

This is called “task-oriented” motivation, which emphasizes a process-based approach to learning and improving as an athlete. When motivation wanes for women, that’s a sign that they could use a reminder on how far they’ve come, where they’re headed next, and what steps they’ll take to get there. Plot the path first. The desire to walk it will follow from there.

Confidence

What athlete doesn’t crave more confidence? But here’s the thing: confidence isn’t something that you can simply will into existence. It’s not even something that you can specifically train from a mental performance perspective. Confidence is simply a side-effect of doing things that demonstrate your capabilities, and doing them often enough to build up a bank of evidence. It’s a byproduct of reinforcement. So to gain more confidence, athletes need to focus on finding reinforcement for their abilities first. And just like motivation, the type of reinforcement that contributes to confidence is different for women than men.

For women, it’s all about the environment. Comfortable, supportive surroundings help mitigate performance anxiety and boost self-assuredness. Where we are, to an extent, but more so who we’re with. Surrounding ourselves with people who provide positive feedback offers our brains the reminder that we’re on the right track.

Research on instilling confidence in female athletes points to the significance of social support for women especially. The trick is to figure out what that support looks like for you. Some people appreciate boisterous commentary from their climbing partners; others get distracted the second someone breathes too loudly in the background while they’re on route and need any words of support to wait until they’re back on the ground. Either way, communication is key. Don’t be afraid to tell your support system what you need based on your definition of support. Knowing the effect that their presence has one way or the other, it’s worth a little assertiveness!

Takeaways on the Physiological and Psychological Differences Between Male and Female Athletes

- The female build translates to greater fatigue resistance and a higher capacity for endurance compared to men.

- The connective tissues within female bodies tend to be more elastic and pliable than those that make up male bodies, which opens up a wider range of motion for women.

- Women tend to sweat less, especially during the high-hormone phases of the menstrual cycle, which makes it tougher for the body to regulate temperature.

- Female catabolic rate increases during high-hormone phases of the menstrual cycle, so women need sufficient amounts of protein paired with carbohydrates to improve protein synthesis for the sake of recovery.

- Women are more susceptible to mental health struggles.

- Stress affects women more intensely, but they are also more adept at managing that stress than their male counterparts.

- Women tend to be more task-oriented than men, who are more outcome-oriented.

- Female athletes gain confidence from social support, positive feedback, and frequent reinforcement of their capability.

Related Articles:

- Differences Between Male and Female Athletes, Part 1: Physiological Differences in Favor of Girl Power

- Amity Warme’s Inspiring Approach to Injury Recovery

- How Elite Boulderer Andy Stull Translates Her Training to Sport Climbing

- Paige Claassen’s Tips for Pregnant and Postpartum Climbers

- Heart of a Champion…and Strength of a Female Terminator!

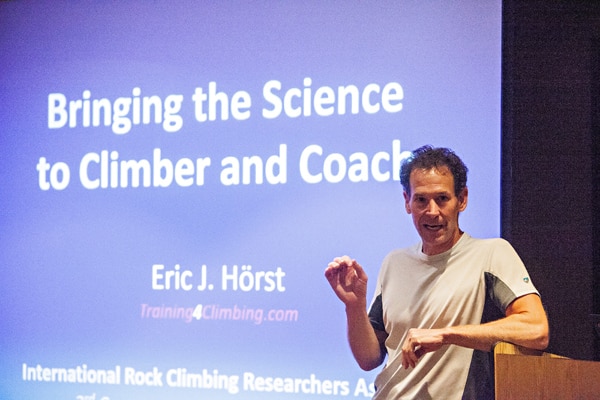

Copyright © 2000–2024 Lucie Hanes & Eric J. Hörst | All Rights Reserved.