The end of one thing means the beginning of another. Embrace the climbing training season as an opportunity to enhance your climbing ability in ways that a performance focus doesn’t leave enough time and energy for. Read on to start creating a climbing routine that will get you through the training season happier, healthier, and stronger than ever before.

Cragging season is winding down across most of the northern hemisphere. As the days become shorter and the temps colder, there comes a point when crispy sending temps morph into a case of the screaming barfies that all the hot rocks and hand warmers in the world can’t cure. And that, my friends, is the sign to start taking your climbing indoors.

It can be hard to transition away from blissful afternoons spent trying hard on real rock and eating snacks in the sunshine with your friends. Outdoor climbing brings us back to the core of our sport in a way that gyms just can’t replicate. For many climbers, it also serves as an escape from the neverending to-do lists and glaring screens that define adult life these days.

But there’s benefit in embracing the changing seasons. Humans aren’t built for stagnancy. Too much of the same ol’, same ol’ will eventually take a toll on anyone’s motivation, energy, and output. We need regular changes in stimulus to avoid plateaus. Transitioning from outdoor performance to indoor training allows both the body and mind to soak in all the effort over the past few months while preparing to do it all again—but better.

Use the training season wisely, and you’ll emerge as a stronger and more psyched climber come spring. Give yourself the gift of a little structure over the next few months. Wandering aimlessly around the gym won’t do much for your physical abilities or mental drive. Build out a training plan that puts purpose behind your time indoors.

Working hard doesn’t always mesh with climbing hard. Cragging season might hold your best performances, but training season is where the growth happens. Shift your focus and make a plan that’ll make your next cragging season the best yet. Photo by Roy Ann Miller.

Outdoor Performance Versus Indoor Training

For climbers who want to take their abilities on real rock to new heights (literally), there should be a stark difference between how they approach their outdoor and indoor climbing time. Outdoor climbing is all about chasing your potential. Sending hard projects requires more than just hard work. In fact, too much hard work during the cragging season will prove counterproductive. Fatigue is not your friend at this time. Try hard, yes, but balance that with resting and recovering just as hard. Peak performance requires showing up at the crag with enough energy to throw down when it counts.

Indoor training, on the other hand, doesn’t involve quite as much coddling. It’s the time to get a little tired and do a little damage. Training inherently breaks the body down. It’ll grow back stronger, but not in time to perform at your peak every weekend—so that’s what winter’s for. Shift your focus toward the things that would sap too much energy during the outdoor season: building strength, bringing your weaknesses up to speed, and increasing your work capacity.

Creating a Climbing Training Routine

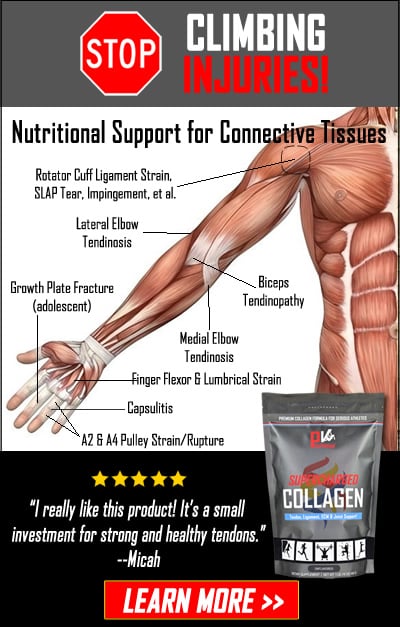

To do that, you need to cover all the bases without also spreading yourself too thin. Many climbers get stuck at one end of this spectrum or the other. They’ll hyper-fixate on one aspect of their climbing, like hangboarding, and train it at the expense of almost anything else. If they don’t get an overuse injury (and that’s a big if) they’ll have stronger fingers, sure…to go along with an utter lack of power and garbage technique.

That’s why smart training plans include a variety of focal points. The most capable climbers take a well-rounded approach to their training so they don’t wind up with such blatant strengths or weaknesses. Be sure to touch on the three major components of climbing throughout your training season: strength, power, and power-endurance.

(If you’re wondering why pure endurance isn’t on this list, it’s not because it doesn’t matter. Aerobic endurance training can make a great primer to a training cycle as a way to build a base of general fitness. It’s also easy to develop at the beginning of a performance season as climbers transition back to long crag days. Strength, power, and power-endurance tend to require more directed attention than endurance. Devote the main course of your training season to these three systems and treat endurance as dessert.)

There are a few different schools of thought as far as structuring time spent on these different energy systems. But the simplest way to go about it is to dedicate a block to each one. Most climbers start with strength because it forms the foundation for everything else. Power follows next, since it’s essentially strength in conjunction with speed. Finish out with power-endurance, which combines elements of both strength and speed. Power-endurance allows climbers to apply both static strength and dynamic power over a longer period of time. That’s exactly what you need for redpointing hard routes and boulders. Concluding a training program with power-endurance prepares climbers best for transitioning back to performance.

Example Training Season Plan

Let’s take a standard three-month training period as an example. Assuming the climber already possesses a base of general fitness, the plan would begin with a three-week focus on strength. This block might include components like…

- Limit bouldering: moves at your absolute limit. Sending doesn’t matter, but rather trying hard sequences in small, intense doses.

- Max hangs: hangboard training on moderately small edges for reps of 10 seconds at a weight that you can maintain for three sets per grip type.

- General strength training: heavy lifting to build full-body strength beyond just your fingers. Think pull-ups, deadlifts, rows, bench presses, overhead presses, and core exercises.

Punctuate the block with a deload week. Cut each session down by 25-50%, and remove one regular session from your week entirely. This relative break gives your body time to absorb the work and recoup energy for the next round.

For the three-week power block, look to include…

- Power bouldering: similar to limit bouldering, but with a strictly dynamic focus. Think big moves on big holds.

- Campus training: strategic ladders and throws from rung to rung on the campus board, or on set boulders without feet. Aim to increase the span and intensity of moves over time.

- Plyometric strength training: explosive movements like jump squats, power pull-ups, and box jumps.

After another deload, the three-week block of power-endurance can consist of…

- Interval climbing: periods of hard work followed by periods of rest. 4×4’s, AMRAPS (as many rounds as possible), and EMOMS (every minute on the minute) all fall into this category.

- 7/53 hangs: hangboard training on moderately small edges for three reps of seven seconds on, 53 seconds off at a weight that you can maintain for two sets per grip type.

- Circuit strength training: rounds of full-body strength exercises with minimal rest in between sets.

Use warm-ups and cool-downs to sprinkle in technique work. This ensures a regular commitment to working your weaknesses and cleaning up your quality of movement alongside targeted training in each of the above arenas.

A structured training season can spell the difference between drudging through winter and finding purpose in it. The time goes faster when you have boxes to check. Come out stronger on the other side of training season—and maybe even enjoy the change of pace in the meantime.

Related Articles:

- Level-Up Your Warm-Up Climbs

- 4 Fingerboard Training Protocols That Work

- 3 Hangboard Tests to Gauge Your Climbing Ability

- 3 Tips for Off-The-Wall Climbing Training

- 5 Training Tips to Climb Effectively

Copyright © 2000–2024 Lucie Hanes & Eric J. Hörst | All Rights Reserved.