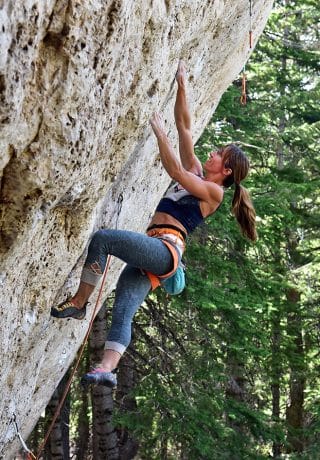

Movement master Carrie Cooper using proprioception to climb strong on the Wild Iris classic, “When I Was a Young Girl….” Hörst photo.

Climbing your best is all about efficiency of movement. Mastering that skill requires tuning into proprioception, a.k.a. the feedback you get from your body in relation to the wall. Learn how to listen to what your body is telling you, and how to tweak your movement to fit the needs of the rock in front of you.

(This article was originally published in August of 2019, but the laws of gravity haven’t changed since then!)

“Process feedback” involves subtle proprioceptive (internal) and exteroceptive (external) cues that constantly change from minute to minute. On a difficult crux move, for example, you might shift your center of gravity toward a high foot placement. This might lead to a loss of balance and difficulty gripping a sloping hold. Based on this proprioceptive feedback from within your body, you twist your hips to position yourself closer to the wall on one side. This results in improved stability, balance, and grip on the rock—and a successful ascent!

This kind of process feedback comes from listening to the sensations in your muscles and joints throughout every move of every climb. But many climbers struggle to achieve this level of self-awareness. Only the loudest, most dire proprioceptive messages (such as My foot is slipping! or I’m about to fall!) register in their conscious mind. Elite climbers, on the other hand, possess acute awareness of process feedback. They can instantly tap into subtle proprioceptive sensations to optimize a foot placement, body position, or movement pattern. Such a high level of self-awareness requires a long-term, conscious effort to understand the physical sensations that spring forth as you climb. It’s worth the time to develop this critical ability!

Dig Deeper

On the macro scale, you must also strive to recognize “gross results feedback”. This type of feedback from your body provides clues about the effectiveness of your actions and chosen strategy. On the surface, gross results feedback seems like nothing more than the outcome of an action, like falling off a move or failing on a route. It doesn’t take much effort to become aware of such a consequence…right? Not really; there’s always a deeper message to be found, if you have enough self-awareness to look for it.

Making the most of proprioception in the form of gross results feedback means searching for the exact cause of a particular outcome. For example, you might ask yourself: Is my limiting constraint mental, technical, or physical in nature? You can then probe even further: Was I climbing too slowly? Is there a better sequence to be found? Is fear preventing me from fully committing to the moves? Keep an open mind as the internal conversation continues, and play the role of a performance detective who’s trying to uncover as many clues as possible.

Fly High

Another strategy to improve self-awareness of results is to take a bird’s eye view of yourself climbing or training. Step back and externally examine the strategies you’ve employed, the ways you’ve been training, and your overall behavior on the wall. From this disassociated perspective you can be more constructively critical in your assessment. Can you identify a flawed strategy? Are you performing the same action over and over, without any course corrections? Are you training ineffectively, perhaps failing to address weaknesses? Do you catch any emotions getting out of hand and adversely affecting your performance?

Emotions commonly cloud self-awareness. An overload of emotion of any kind—even confidence—not only overwhelms subtle proprioceptive feedback, but can also cause you to miss the even more blatant gross results feedback. That’s because ego and self-awareness tend to be mutually exclusive. The very best climbers often adopt a humble, quiet demeanor that enables them to remain curious, introspective, and highly self-aware. They are fueled by a constant curiosity to discover what optimal movement is and feels like for them.

Movement Mastery Tip:

Don’t thrash up a boulder problem or route once and call it “good enough”. Make it a habit to re-climb the problem or route a few more times (in the same session or the same week) for the sake of proprioception training. Aim to refine and improve the quality of your movement with each additional ascent. Focus on:

1. The feeling of doing the crux move(s) in the most efficient way

2. The feeling of optimal center of gravity positioning for each move

3. The feeling in the muscles you must either contract or relax in order to flow through the sequence most efficiently.

Achieving the next grade or doing the ‘impossible’ is a battle fought more in the mind than in the body.

Related Articles:

- The Power of Proprioception

- 4 Steps to Improve Your Quality of Movement and Climb Harder!

- Mental Mastery Skills to Stretch Your Limits

- 10 Mental Strategies to Improve Performance

- 4 Tips for Becoming a “Head Strong” Climber

Copyright © 2000–2023 Eric J. Hörst | All Rights Reserved.